With most people flocking to Australia’s coastline to bask on beautiful beaches and enjoy a modern urban lifestyle, it may seem that there’s ‘bugger all’ there in Australia’s Outback. We’d encourage you to take another look, as not only is the Outback home to an amazing array of creatures, some 1,500 communities including the Anangu people, but also to Uluru, a giant rock of sacred reverence, representing the heart of Australia’s rock solid centre. Read on to share in Liz’s extraordinary adventure of a lifetime responding to Uluru’s sacred call.

Sir Alec Issigonis, designer of the Mini, famously described a camel as a horse designed by committee. What might he have said about a kangaroo? Even in its home country, Australia’s iconic animal is not even close to being the most curious of creatures. In fact, more than 80% of Australia’s plants, mammals, reptiles and frogs are found nowhere else in the world. Charles Darwin, who never actually saw a kangaroo, described “the strange character of the animals of this country as compared with the rest of the world.”

Discovering Australia’s Outback

Australia itself is no less unique than its inhabitants. It is the lowest, flattest, and oldest continental landmass on Earth. While most of the human population basks on beautiful beaches and enjoys a modern urban lifestyle around the perimeter of this island continent, life can be precarious in the 2.5 million square miles in the middle – the Outback. It’s also called The Bush, though with only 20 inches of rain annually, there’s very little actual bush. My mildly blasphemous Great Uncle Bob, who immigrated to Australia after WWI, used to call it GABA – the Great Australian Bugger All – an expression, I discovered, that is still in use today.

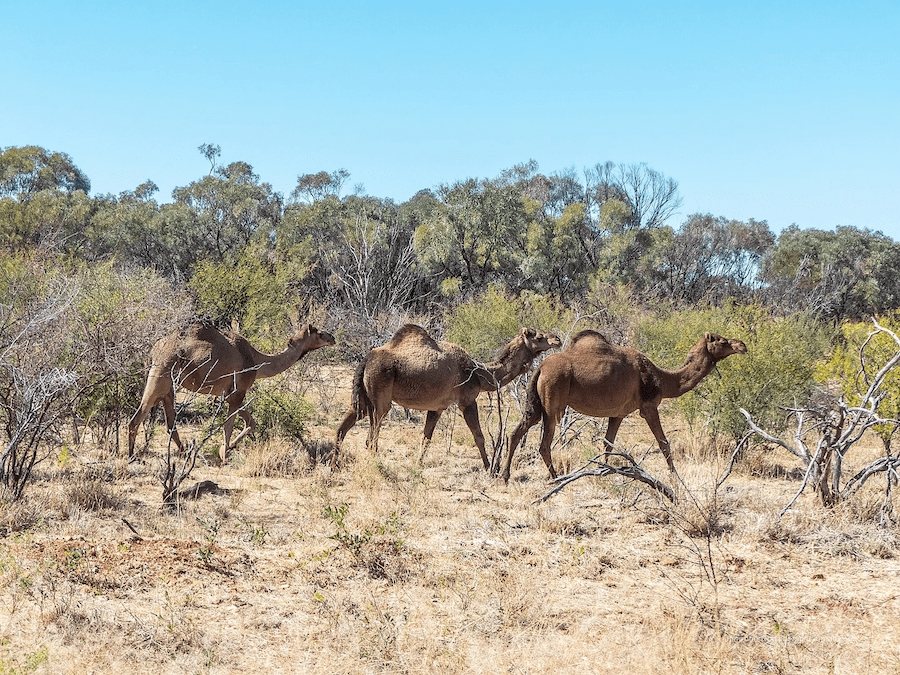

But while it may seem that there’s ‘bugger all’ there, the Outback is actually home to an amazing array of creatures – red kangaroos, wallabies, dingoes, skinks, frilled neck lizards, and much more. And some 1,500 communities, mostly aboriginal, have called it home for millennia. The Anangu people have lived around Uluru, in the middle of the Outback for about 40,000 years. And the giant ‘rock’ which bears that name is a sacred place to them.

Uluru, a Sacred Heart of the Outback

Uluru or Ayer’s Rock stands sentinel-like in the midst of sand and dry scrubland. During the long, four-hour bus ride from Alice Springs, this makes for little scenery of note. But then the driver, Martin, stops in what seems the middle of nowhere. He points up a sand hill, “Go up there.”

It’s very hot, but several of us leave the air conditioned comfort of the bus to dutifully clamber up the dusty path. What we see is extraordinary!

In the midst of red sand and scrub, sprawls an expanse of what looks like winter ice on a frozen lake. But the hot sand beneath my sandals contradicts my senses. Martin explains that this is actually one of hundreds of salt lakes that dot the region, the largest being Lake Amadeus, just north of Uluru, which covers more than 1,000 square kilometres. “This was part of an inland sea so the ground water here is salty,” he adds. “Actually, the salt in some areas is so thick you can drive on it.”

I’ve already concluded that the decision to take this long bus ride was a good one when Martin stops again. And for the first time, I see Uluru looming in the distance, like a giant loaf fresh from the oven. Measuring 348 m (1,140 ft) high and 9.5 km (6 mi) in circumference, Uluru is the largest sandstone monolith in the world, dominating the landscape, even from this distance.

Standing 19 km from it in Uluru Kata Tjuta National Park, her sister monolith, Kata Tjuta, is made up of 36 giant domes spread over more than 20km (12mi). This massive pair holds great spiritual significance as the place where many Indigenous creation stories converge. And it’s a significance the Australian government has recognised. In 2000, in acknowledgement of its symbolic importance to the country, the Olympic torch began its journey in Australia by circling the base of Uluru. And the 2019 ban on climbing Uluru affirmed its spiritual importance to the indigenous people.

In the past, climbing Uluru was THE challenge for thousands of visitors. The climb was 1.6 km straight up, and without a toilet, many simply relieved themselves at the top. Most indigenous people saw this as a desecration, pointing out that this is no less appalling than would be this treatment of an important Buddhist temple, or a mosque or a church. It should be noted too, that while thousands have scaled the same steep path to the top, many have been injured, and some 38 people have died attempting it. For the Anangu, this path, still clearly visible as a bleached scar on the red sandstone, has added sadness to their sacred place, and they ask that it not be photographed.

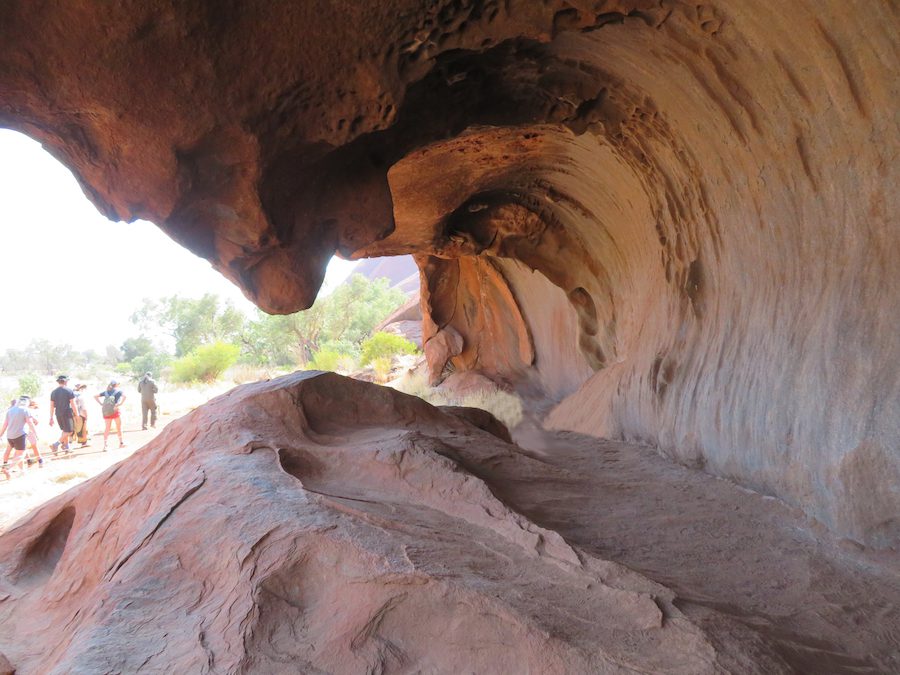

Today, one can take a walking tour around the base of Uluru with an indigenous guide. Our guide points out a deep waterhole at the base of Uluru which is replenished by a waterfall. This is the “Sacred Waters” and this precious source of water has been crucial for survival to desert dwelling animals of Australia for millions of years, as well as to Aboriginal people making this area their home.

It can be a harsh home – dry and unforgiving but they have learned to thrive in it. An elder tells me, “We don’t try to control the world, we live in it and adapt to it.” This is significant he adds, as “this is born of respect for nature and a desire to protect it.”

In Uluru’s base there are caves and crevices. One is a kitchen area; another is the men’s area; and yet another is sacred to women. There is a strong social order and cherished history. There is rock art, estimated to be 12-14,000 years old. And there are stories, passed down through the generations, says the elder, “Our religion was never written down, but our elders keep the stories alive.”

The Anangu believe that the shapes and textures of the unique geologic formations in Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park hold knowledge and stories which are still relevant today. One of the earliest stories is of the Mala people who settled near Uluru, and the devil dog Kurpany, who tried to destroy them. And a new way of telling this story is the main reason for – and the highlight of – my visit to Uluru.

Wintjiri Wiru, sharing a chapter of the ancient Mala story from Kata Tjuta to Uluru

In May 2023, Voyages Indigenous Tourism Australia launched Wintjiri Wiru, which means ‘beautiful view out to the horizon’ in the local Pitjantjatjara language. This extraordinary, fully-immersive light and sound show uses more than 1,100 drones to tell the ancient Mala creation story. It’s the first time a light, laser, projection and drone experience of this magnitude has been performed on a regular basis anywhere in the world.

We start on a terrace built in the bush to take advantage of views of the setting sun dappling Uluru in one direction and Kata Tjuta in the other. I sip a refreshing cucumber cooler made with Beachtree Gin (an Indigenous-owned distillery), and sample some very unusual appetizers: mini sweet potato flan served with scattered wattleseed crumbs; a ginger infused cucumber spear sprinkled with green ants; lemon myrtle crocodile curry tart.

The colours change as the sky darkens. We take food hampers, filled with more unusual flavours, to seats in an amphitheatre built into a natural hollow, and decorated with iconic indigenous designs.

I watch Uluru fading into the deepening night while I nibble local cheeses; blackened pepper leaf kangaroo; shrimp Waldorf salad; smoked emu with saltbush chili crust; and jams made of quondong and Davidson plum. Dessert is lime tart sprinkled with green ants. I taste everything – yes, even the ants!

But as darkness falls, food is forgotten. A round moon rises in the distance but the land before me turns into blue ocean waves, then glowing flames, and the riveting Mala tale unfolds. The battle rages and a giant Kurpany, created from hundreds of drones, looms before us. The story is recounted in both Pitjantjatjara and English, highlighted with a powerful, haunting song.

Even as the last drones finally fade away, leaving a desert sky filled with stars and constellations, the bright moon seems to echo the music. And in the distant darkness, Uluru stands, solid and enduring.

Before dawn I hike to the lookout near the Outback Hotel to see the two sister summits waken to the first rays of the rising sun. Alone in this barren landscape, it’s easy to understand the awe these monoliths inspire; they dominate the world around them. I hear the scrabble of some desert creature nearby and privately hope it isn’t a nasty snake into whose home I have trespassed. After all, Australia is home to some unpleasant reptiles. But it seems to move away, and so do I. Breakfast awaits and later, a bus back to Alice Springs.

I take away the memory of hot, red sand and scrub bushes; spectacular sunsets and dark skies filled with constellations; and these two ancient megaliths demanding my attention.

It’s clear why this area is so significant to the people who have inhabited it for thousands of years. It is very special to walk on this land; to listen to the stories of those who have lived here for thousands of years; and to stand in awe before a rock so huge, it actually extends 2.5 kilometres below the spot where I stand. This is the heart of Australia’s ‘great bugger all’ and its beat is still strong.

Disclaimer: There are affiliate links in this post. If you make a purchase after clicking on one of these links, we may receive a small commission at no extra cost to you. This commission contributes to paying our writers for their storytelling. We only post links to things that we ourselves have tried.

Arlene Phillips

We have been to Uluru and walked the base with a guide. We were very fortunate to be there when there was a tremendous rain storm and the water cascaded off the rock in waterfalls, only to dry up and go away in a matter of an hour or so. We have not heard the story of the Mala People and Kurpani , the devil dog Thank you for sharing. We would love to see that show next time we go. So many drones! Very well written and informative article Liz.

Liz Campbell

Thank you for your kind words. I would have loved to have seen the sudden rain. I think it would have been very dramatic and a very special benison.