Once in the shadows of Canadian history, the Chinese Canadian Museum in Vancouver, BC shares the stories of Chinese Canadians, beginning with the museum’s inaugural exhibition, The Paper Trail Project to the 1923 Chinese Exclusion Act, where writer Jacqueline Louie discovers some of her own family’s history.

The history of people of Chinese ancestry in Canada reaches back to before Confederation — yet the stories of Chinese Canadians seldom take centre stage.

Chinese Canadian Museum

The Chinese Canadian Museum in Vancouver aims to change this by spotlighting the stories of Chinese Canadians. Located in the historic Wing Sang Building on Vancouver’s Pender Street, the Chinese Canadian Museum is dedicated to sharing Chinese Canadian history, since opening its doors on July 1, 2023 — the centenary of the 1923 Chinese Immigration Act, also known as the Chinese Exclusion Act.

The Chinese Exclusion Act

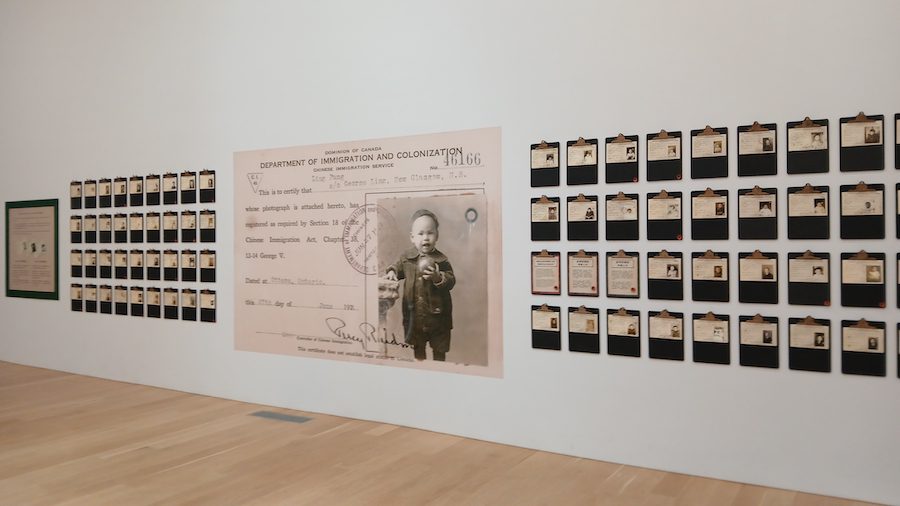

The museum’s inaugural exhibition, The Paper Trail to the 1923 Chinese Exclusion Act, is a national archive and first-of-its-kind exhibition in Canada, displaying immigration certificates crowdsourced from Chinese Canadian families from across Canada.

The Chinese Exclusion Act is a monumental chapter in this country’s history, yet it is forgotten.

~ community historian Catherine Clement, Paper Trail exhibition and project creator and curator.

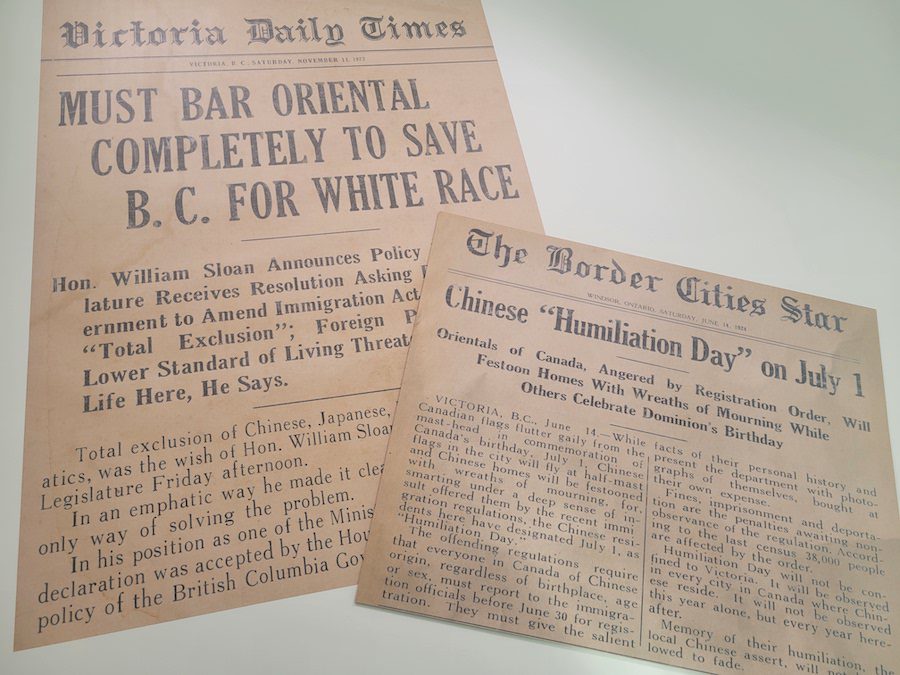

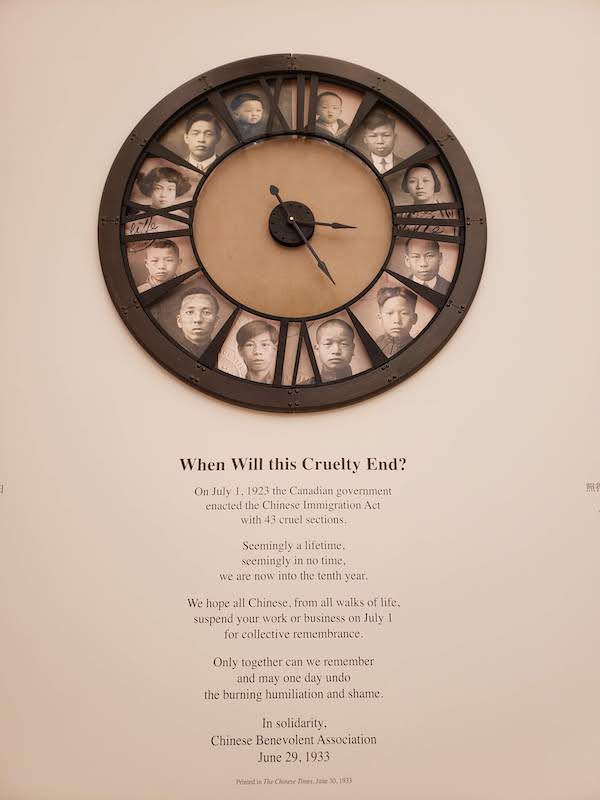

The Chinese Immigration Act virtually suspended immigration from China to Canada from 1923 – 1947. People of Chinese ancestry were the only group who faced this type of legislation, based solely on their ethnicity. The Act required all people of Chinese ancestry, including children born in Canada, to register with the Canadian government. If someone didn’t register, they faced a huge fine or could be thrown in jail.

No other immigrant community to Canada was subject to the same amount of documentation as the Chinese, Naomi Louie says. At the same time, she adds, there was also a broad intersection in the way that documentation was used by the government to surveil and control different groups of people. During World War II, for example, approximately 22,000 Japanese Canadians— a majority of whom were born in Canada and were British subjects — were interned.

… and Indigenous people were subjected to a pass system, requiring documentation to move between reservation and non-reservation land, beginning in 1885, shortly after the end of the Northwest Rebellion, and the same year the government enacted the Chinese Exclusion Act.

The Paper Trail Project

The Paper Trail Project tells the story of the Chinese Exclusion Act through Chinese Immigration certificates — a paper trail back through time. “This is one of the best places to get that story, and see the individual stories of people who lived through it,” says Naomi Louie, museum assistant at the Chinese Canadian Museum and a curatorial assistant on the Paper Trail Project. “This is the first time the national story of the Exclusion Act has been told in a museum. Every story, with a small handful of exceptions, comes from documents submitted by Chinese Canadian families.”

This exhibit is like nothing I’ve ever seen before. Documents with photos, face after face of men, as well as some women and children, looking out from Dominion of Canada Immigration certificates noting their entry to Canada or birth in Canada. One of the certificates on display is my grandmother’s, whose picture shows her as a young girl. Even though she was born in Canada, she had to have a Chinese Immigration certificate. Each man, woman or child of Chinese ancestry who held one of these certificates was required to show their certificate to exit or re-enter the country or if immigration officials demanded to see their papers.

The Paper Trail Project is not just a museum exhibit: its major legacy will be its archives, created in partnership with the University of British Columbia, to archive, collect and make publicly available, scans of Chinese Immigration and Head Tax certificates, to future generations of researchers.

I sit down at an old-fashioned wooden desk, part of the exhibit, which includes more stories to peruse. I flip open a binder that lists the names of Chinese immigrants to Canada and their dates of arrival; a shiver runs down my spine when I find the name of my grandfather, who arrived in Calgary, from southern China, in the spring of 1899.

In addition to the main exhibit areas, there’s a smaller room where visitors can sit down to watch two short films: Remembering Chinese Bachelors and Stories of Repeal and Reunion. There are also photos and stories of Chinese bachelors in Canada, and how the Chinese Head Tax and Chinese Exclusion Act impacted their lives. Many men were separated for decades from their families in China because of Canadian legislation, which caused an extreme gender imbalance; in 1923, the ratio of Chinese men to Chinese women in Canada was 35:1.

As I walk through a narrow hallway in the exhibit, look at these men’s images and read about their lives, I end up weeping at the injustice of it all, and the tragic turn that some of their lives took when the Chinese Immigration Act was enacted.

This exhibit is for all Canadians, not just those of Chinese ancestry, says Naomi, who is mixed race, of British and Chinese heritage. “This is a story that most people can, in some ways, see themselves in. For most of us, unless you’re Indigenous, then your family immigrated to Canada.

The Paper Trail exhibit is for all Canadians, not just those of Chinese ancestry. This is a story that most people can, in some ways, see themselves in. For most of us, unless you’re Indigenous, then your family immigrated to Canada.

~ Naomi Louie, museum assistant at the Chinese Canadian Museum and a curatorial assistant on the Paper Trail Project

In addition to the Paper Trail Project, which occupies the second floor main gallery, the Chinese Canadian Museum also includes a variety of other exhibits. During my visit Reshaping Collections: Where History Meets Art, recently opened on the first floor. On the third floor, you’ll find the Wing Sang building’s recreated school room, where Yip Sang, a Chinese Canadian merchant and the building’s owner in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, opened a school “to provide education for his many, many kids and for the other kids who lived in the neighbourhood,” Naomi says.

The Paper Trail exhibition is open through the end of December 2024, and you can discover other future and current exhibits by visiting the Chinese Canadian Museum website.

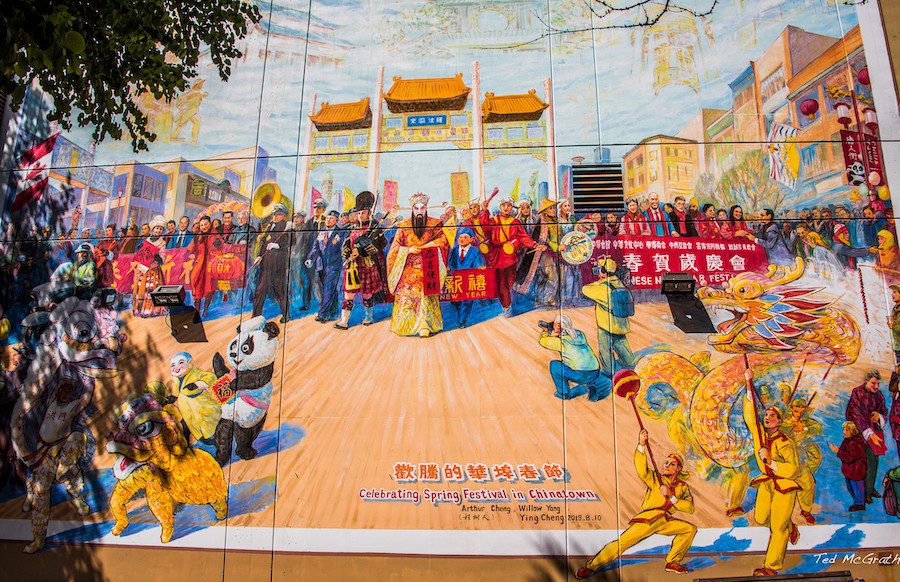

Exploring More of Vancouver’s Chinatown

“Chinatown gets a bad rap. If you go in the daytime, there’s so much beauty here, so much vibrancy. There have been so many efforts to revitalise the area,” says Naomi Louie. In addition to the Chinese Canadian Museum — located in the Wing Sang building, the oldest building in Vancouver’s Chinatown at 51 East Pender Street — there’s also the Chinatown Storytelling Centre, at 168 East Pender Street, which tells stories of the Chinese Canadian journey and Vancouver’s Chinese community.

“New bakeries and eateries are all part of this beautiful cultural landscape. We have everything from Hong Kong-style cafes, to classic dim sum places. It’s a great historic place to spend some time in,” Naomi says.

Vancouver, BC Accommodations Map

Planning a visit to Vancouver, BC, Canada? Check out this interactive map to different accommodations available in and around Vancouver.

Disclaimer: There are affiliate links in this post. If you make a purchase after clicking on one of these links, we may receive a small commission at no extra cost to you. This commission contributes to paying our writers for their storytelling. We only post links to things that we ourselves have tried.

What a powerful contribution–thank you Jacqueline Louie!

Thank you for reading and caring Kirsty!

It’s so sad to reflect on the “total exclusion of Chinese and Japanese people” from BC – newspaper from 1923 that highlights this painful chapter in history. The name “The Paper Trail Project” is very symbolic! The story through paper immigration certificates.

I’m curious, if there were any nationality to exclude (for any reason), who would it be? This is just a rhetorical question, but it prompts to confront our biases. Can history repeat itself in different forms?

Thank you, Jaqueline , for reminding us of this important issue. It’s a great project!

Thank you, Kate, for your comment and for reading my story about this chapter of Canadian history!