Join us on the Culture Travels Podcast (recorded live in studio on the Fireside Chat App on February 5, 2022), as we share a delicious Pumpkin Mochi Cake recipe, bake together and immerse ourselves in Japanese Canadian Culture and Traditions! This episode is a celebration of culture, family stories, and baking adventures. Join Manami Calvo, middle schooler Maya Calvo, and Erica Hargreave as they share tips and tricks for making this unique treat while exploring the rich heritage of mochi making, its connection to Japanese New Year, and family traditions passed through generations.

As is the case when you are hanging out in the kitchen and baking and chatting with friends, this is one of our longer episodes of the Culture Travels Podcast, so we have broken up some of the themes of the episode below, along with including time markers for ease of finding our conversation on specific topics within the episode.

We also have a video version of this podcast, which is less edited (so about 20-minutes longer in length). The time markers in this post, match the audio podcast above and not the video edit below.

What is Mochi?

Mochi, for those of you have yet to indulge in this sticky rice treat, is a Japanese rice cake made by pounding glutinous rice into a paste and sometimes mixing it with other ingredients, before moulding it into different shapes.

In Japan, as Manami fondly reminisces, mochi can be bought throughout the year from street vendors, but for her family in Canada, it is typically a dessert made for special occasions, as if it is to be eaten before it dries, it needs be eaten within a day or two of it being made. In Japan, mochi is a traditional food for the Japanese New Year (which is celebrated on January 1st).

Traditionally mochi is made in a ceremony called mochitsuki. In this ceremony, glutinous rice is pounded into a paste using a wooden mallet in a mochi bowl (think large scale pestle and mortar). To keep this tradition alive, and teach younger generations about their Japanese heritage, the Nikkei National Museum and Cultural Centre in Burnaby, BC hosts an Annual Mochitsuki Day (around New Years) where people can come take part in a traditional mochi making ceremony. This is where Maya first made mochi.

The video below was shot by Burnaby NOW at a past Mochitsuki Day at the the Nikkei National Museum and Cultural Centre.

While Maya and Manami have typically enjoy mochi fresh and as a sweet treat, it can also be cured and dried for later use, and it can be enjoyed in a soup, toasted, served with vegetables and seaweed, and dipped in condiments like soy sauce. Mochi might also be filled with red bean paste, peanut butter, matcha and more. To give you an idea of the large variety of types of mochi, below are just a few different types of mochi:

- Daifuku – round in shape and filled with a sweetened bean paste.

- Sakura (cherry blossom) – round ball shaped mochi that has a lumpier texture, as it contains some whole rice grains, and is served with a salted sakura leaf.

- Warabi – a translucent mochi that has a soft, jelly texture, and is mostly found in western Japan. Warabi mochi is made from warabi starch, which comes from a type of fern.

- Hanabira (flower petal mochi) – hanabira mochi is rolled out into a small circle, folded in half and served with white bean paste, miso, and a candied stick of gobo burdock root.

- Hishimochi – colourfully layered mochi, that are cut in a diamond shape, symbolising good health, long life, fertility, and new life.

- Botamochi or Ohagi – mochi rice ball with both chunky and smooth red bean paste inside.

- Kirimochi or Marumochi – unsweetened mochi, cut into rectangular blocks and packaged once in its hard dried form for later use in cooking.

- Kusamochi – a green mochi made from a mixture of sticky rice and yomogi (a Japanese mugwort plant), which is shaped like a flower and filled with red bean paste.

- Kuzumochi – a clear mochi that is made with the starch of the Japanese arrowroot plant and mixed with whole red beans or topped with sweetened red bean paste.

Over time, as the culinary creative do, people have altered the different types of mochi to create new versions of popular forms of mochi. One such example would be fruit daifuku.

History of Mochi

Perhaps one of the reasons why there are so many different types of mochi and ways of eating it, is that it has been getting prepared and enjoyed for centuries. While the process of steaming glutinous rice and making it into a paste is believed to have its origin in ancient China, it is suspected that was introduced to Japan after rice cultivation at the end of the Jomon period (14,000–300 BC), leading to mochi. Archaeological evidence suggests that home production of mochi increased beginning in the Kofun period in 6th century, when earthenware steamers became popular in households in eastern Japan.

With mochi’s long history and position as a food at celebrations, it has become a part of Japanese legends and folklore.

One such legend was recorded in Bungo no Kuni Fudoki, ancient reports from Bungo Province written in the Nara period (710 until 794 AD) on provincial culture, geography, and oral tradition presented to the reigning monarchs of Japan. As legend has it, when a rich man made a flat mochi from leftover rice and shot an arrow at it, the mochi transformed into a white bird and flew away. After that, the man’s rice field became desolate and barren. This legend has been equated with the superstition that round white mochi holds spiritual power.

Okagami, a historical tale that covers Japanese history between 850 to 1025 AD during the Heian period, shares that mochi was often used in Shinto events to celebrate childbirth and marriage. Emperors and nobilities would put mochi into the mouths of babies that were 50 days old, and it became customary in the aristocratic society for the bride and groom to eat mochi together at the bride’s house three days after the wedding. Despite Manami being a goddess in my heart, it seems she failed to follow this tradition after her wedding. So while a tradition of the aristocracy, perhaps it is not of the deities.

It is also during the Heian period when the first accounts of mochi playing a role in New Years celebrations have been found. Nobles of the Imperial court believed that long strands of freshly made mochi symbolized long life and well-being, while dried mochi helped strengthen one’s teeth.

Later in the Muromachi period (1336 to 1573 AD), the custom of kagami mochi (mirror mochi) began among the samurai class. Kagami mochi are the iconic mochi that we think of today in relation to the Japanese New Year. These are stacked mochi, composed of two spheres that are topped with a bitter orange. To welcome the New Year, it became a tradition for samurai to decorate kagami mochi with Japanese armour and Japanese swords, and place them in the tokonoma (an alcove in a traditional Japanese room where art or flowers are displayed) to pray for the prosperity of their families in the New Year. When people eat kagami mochi after the New Year, they must avoid cutting the mochi with a knife, as that would violate the kami (deities of the Shinto religion). Instead, the mochi is smashed with a wooden hammer after it has naturally dried and cracked. This tradition continues today with the kagami mochi placed on family altars (kamidana) on December 28 each year.

Maya’s Favourite Pumpkin Mochi Cake Recipe

This is the recipe for Pumpkin Mochi Cake that Maya shared with us on the podcast. A recipe which made a most delicious batch of pumpkin mochi cake, as observed by my incessant eating at the end of the episode, as well as approval from Linus the Golden Retriever, my mom, and all the neighbours we shared them with (so as to eat them all while they were still fresh). Just thinking about them makes me want to make more!

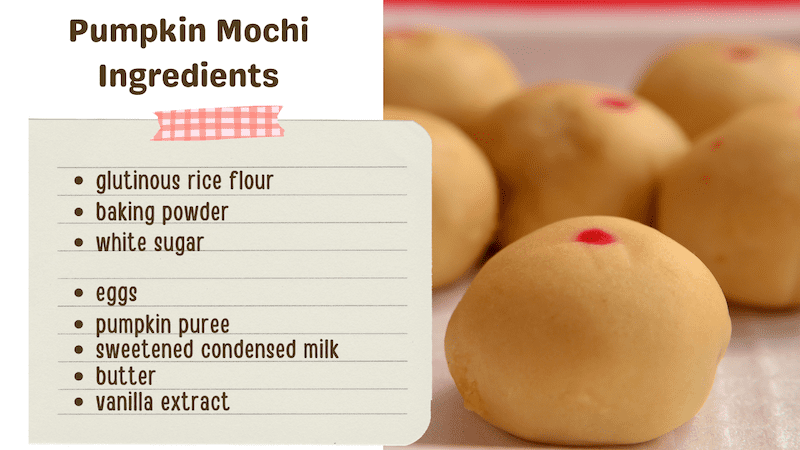

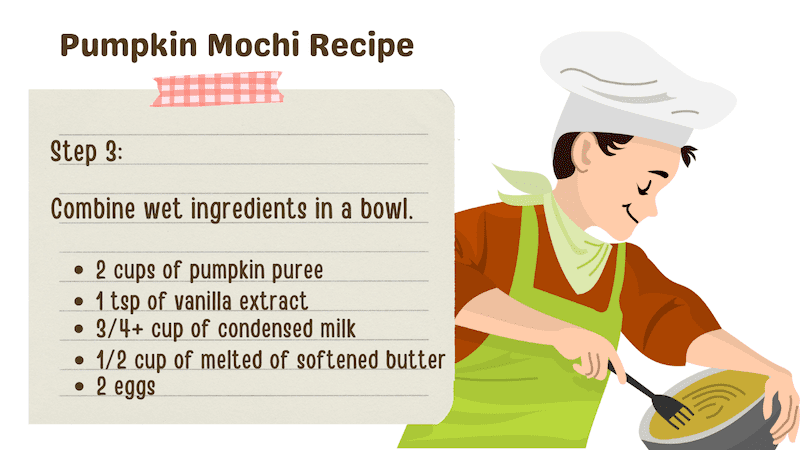

Pumpkin Mochi Cake Ingredients (Time Marker 2:02)

- 1 1/4 cup of glutinous rice flour

- 1 cup of white sugar

- 1 tsp of baking powder

- 2 cups of pumpkin puree

- 1 tsp of vanilla extract

- 3/4+ cups of condensed milk

- 1/2 cup of softened or melted butter

- 2 eggs

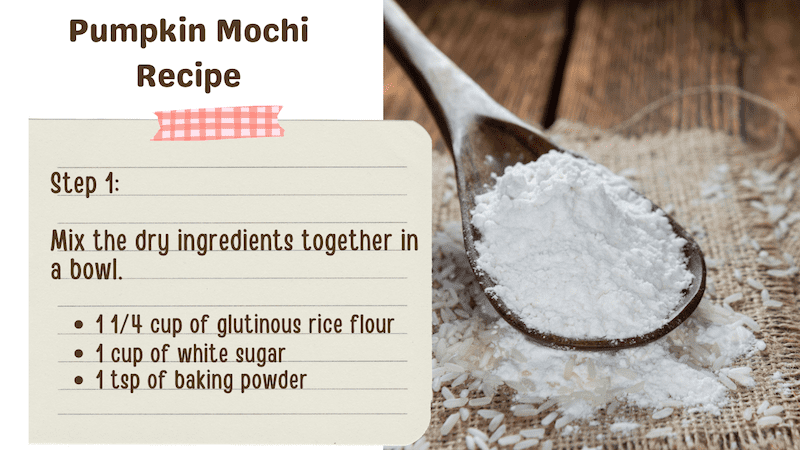

Step-by-Step Pumpkin Mochi Cake Recipe

- Mix the dry ingredients together in a bowl.

- Preheat oven to 350 degrees.

- Beat wet ingredients in a bowl.

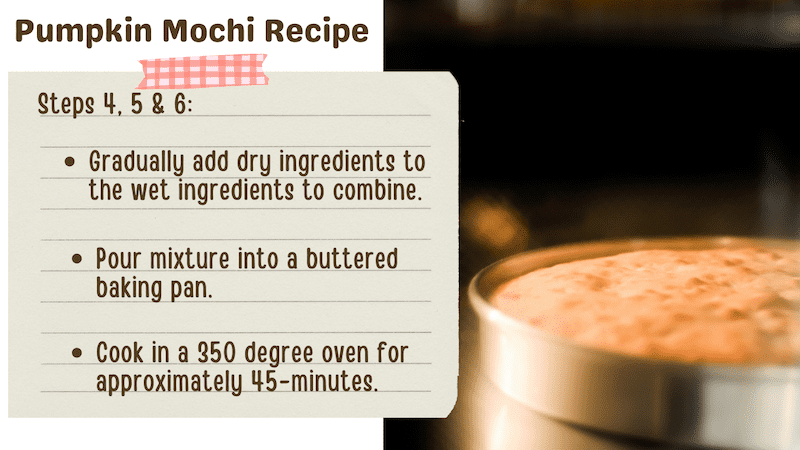

- Gradually add dry ingredients to the wet ingredients to combine.

- Pour mixture into a buttered baking pan.

- Bake in a 350 degree oven for approximately 45-minutes.

- Once golden brown on top, take out and let cool for about an hour before serving.

- Enjoy, and be sure to share, as this mochi needs to be all eaten in the next day or two.

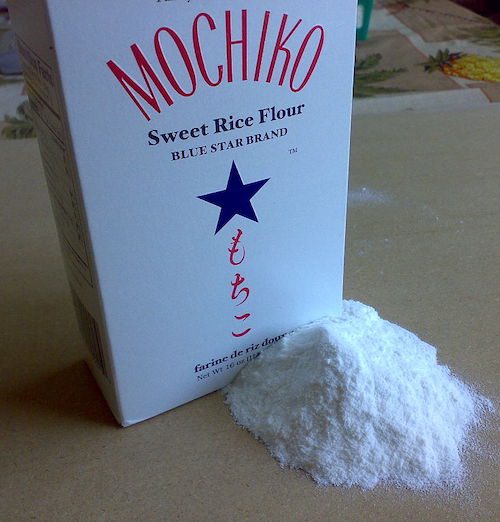

Sourcing Japanese Ingredients in Canada

While we are becoming more and more fortunate in Canadian city centres to be able to find an ever growing selection of Japanese foods in our grocery stores, often we need to go in search of specialty stores for specific ingredients, like Japanese Glutinous Rice Flour.

A few stores mentioned in this episode, where Japanese foods can found in North America include:

- T & T Supermarket (in BC, Alberta, Ontario and Quebec)

- Nations Fresh Foods (in Ontario)

- Amazon International Food Market (online)

- Trader Joe’s (in Washington State)

Nikkei National Museum and Cultural Centre

Aside from what they learned from older generations of their family, both Maya and Manami first began learning about their Japanese heritage through Japanese school at the Nikkei National Museum and Cultural Centre. This is a museum and cultural centre in Burnaby, BC that is focused on honouring, preserving and sharing the history and heritage of Japanese Canadians and Japanese culture in Canada.

The word Nikkei refers to people of Japanese ancestry who live outside of Japan.

Nikkei National Museum and Cultural Centre provides a wealth of programs, events, exhibition, education, research, and other resources for the public to learn and discover more about the history and heritage of Japanese Canadians.

As mentioned in our podcast, one of the events that the Nikkei Cultural Centre launched in 2021 in response to COVID-19 is the Nikkei Garden Farmers Market, which happens on the 2nd and 4th Sunday of each month from July to October. They describe this endeavour as “fostering a healthy community in Burnaby — with a Japanese flair.” Describing the Nikkei Garden Farmers Market as having “a unique Japanese flavour to it — where, you can pick up Japanese vegetables, treats, and handmade products.” While all artisans are invited to apply, to keep with the market’s theme Japanese culture-related items, primary producers and Nikkei non-profit organizations are given priority.

To compliment the market, visitors are invited inside the Nikkei National Museum and Cultural Centre to enjoy the exhibits and seasonal Japanese cultural activities.

Japanese Language Learning with Maya

One of the aspects of the Japanese School that Maya attends at the Nikkei National Museum and Cultural Centre is language learning, so that she can communicate with her grandmother and other family members in Japanese. She kindly taught me a few basic phrases in Japanese throughout the episode, including:

Konnichiwa

Konnichiwa is “Hello!” in Japanese.

Ogenki desuka?

Ogenki desuka? is Japanese for “How are you?”

Hai, genki desu

Hai, genki desu is Japanese for “I am fine” or “I am well.”

Arigatou

Arigatou is “Thank you” in Japanese.

Sayounara

Sayounara is “Goodbye” in Japanese.

Arigatou! Thanks for tuning in and reading!

Sayounara! Until next time, my friends!

Wow. There is unity in diversity. These are beautiful cultures that increases my interest in visiting my Japanese friends someday. Cheers to an educative podcast.

#dreemerforlife

Thanks so much. I feel so very fortunate to have friends like Manami and Maya, who are willing to share their cultural heritage with me.

Hi Erica!!!

I LOVE mochi – and I’m so gonna try this recipe hehehe