At first glance, South Carolina’s Lowcountry conjures images of white-washed walls, rocking chairs, and the opulence of Scarlett O’Hara’s storybook world of life as a Southern Belle on a plantation. It might surprise you then to discover that the wealth of those plantations have their roots in Africa, along with much of South Carolina’s rich history, culture, and cuisine. Read on as Liz discovers the riches of South Carolina’s Lowcountry.

Tune Into Roamancing Reads & Listen to Liz Read Her Article

White-washed walls frame tall, mullioned windows. Rocking chairs offer a comfortable resting place on a deep porch lined with handsome Doric columns. Nearby, live oaks are dramatically draped in Spanish moss. At Hampton Plantation House, the scene is set – enter Scarlett O’Hara.

In fact, says the guide here, although it was filmed elsewhere, Vivien Leigh and Clark Gable actually visited this elegant house before filming Gone with the Wind, and its grand Georgian architecture can be seen in the background of the original vinyl cover of the film soundtrack.

First built in 1735, it’s evident that the Horry family lived in great comfort at Hampton Plantation, supported by a large population of slaves. They and later owners, the Pinckney and Rutledge families, all boasted links to politically and economically prominent South Carolina families. The last private owner of the property was actually Archibald Rutledge, the state’s first poet laureate.

Today, Hampton, now part of a state historic site, is one of the last remaining rice plantation homes in South Carolina. The fact that its wealth was built on rice, rather than tobacco or cotton, might seem surprising. History books rarely mention rice. But while cotton and tobacco were important crops further south, here in the Lowcountry, it was vast rice plantations which created enormous wealth, and launched the elegant Southern plantation culture.

Extending along the Eastern US coast from Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, to Savannah, Georgia, the area known as the Low Country, or Lowcountry, is renowned for its dune-swept barrier islands, its salt marshes, its venerable live oaks draped in Spanish moss, and its distinctive African American cultural heritage. Here, once you leave the aroma of cotton candy and crab legs in Myrtle Beach, the air is scented with the tang of salt water, the earthiness of pluff mud, and the mustiness of Cyprus marshland.

“There were 175 plantations in the Lowcountry and in the 1800s; Georgetown County was the number one rice growing area in America,” says Kevin Jayroe, a guide with Swamp Fox Tours in the city of Georgetown, just south of Myrtle Beach. “In fact, this county was once the wealthiest county in the US, and South Carolina was the second richest state.”

The city today is quaint and charming, its waterfront boardwalk lined with shops and restaurants. But remnants of that early prosperity remain in the Georgetown Historic District, where 63 homes proudly display the blue plaque that marks each as Antebellum (built prior to the Civil War), and listed on the National Historic Register. Jayroe’s tour includes colourful stories of the owners of these homes.

He points out the home of Joseph Hayne Rainey, born to slaves who purchased their freedom. He would become the first Black member of the U.S. Congress.

We pass the home of the Robinson family, grandparents of First Lady Michelle Obama, who were active members of the nearby Bethel AME Church, founded in 1865 by freed slaves. Her great great grandfather, Jim Robinson, was a slave at nearby Friendfield Plantation.

But most of these homes were built by wealthy plantation owners. The 1775 home of Mary Man, daughter of the owner of the once huge Mansfield Plantation, was actually built with timber and labor from their plantation. Though they had property in Charleston, many plantation owners maintained a residence in Georgetown – a major seaport during the 18th and 19th centuries and a commercial hub of the state.

The 1750 home of another plantation owner, Robert Stewart could legitimately post a sign saying, “George Washington slept here.” Stewart hosted the future president, who patently thought Georgetown was an important place to visit. Nearby stands the Freemason’s lodge, where he spoke when he came here. (Washington was a Freemason.)

But there’s a mystery here. The origin of all this plantation wealth remains obscure because curiously little is known about how rice cultivation began. One tale claims a Dutch sea captain paid for goods with rice, but according to the Georgetown Rice Museum, it was more likely that slaves from West Africa brought this grain to America. In fact, these captives introduced millet, sorghum, black-eyed peas, muskmelons, okra, and Guinea squash – common crops in West Africa – and these remain part of the African American culinary tradition.

Nonetheless, their most significant contribution was probably rice, which had been grown on the Rice Coast of West Africa for centuries. Indeed, the success of South Carolina’s plantations would rely heavily on the skill as well as the hard labor of West African slaves who drained swampland, cut down giant cypress trees and created the first rice fields. It was their knowledge of its cultivation and tidal irrigation that made rice one of the most successful crops in early America. Indeed, the 1810 census indicates that the 20,000 slaves then working in Georgetown County made up 85% of the local population!

The abolition of slavery in 1865 brought a slow decline to this labor intensive industry, and hurricane winds in the early 20th century sealed the fate of many plantations, as salt water flooding destroyed the land for rice cultivation. These huge tracts of land were then sold cheaply to the Vanderbilts, Carnegies, and other wealthy industrialists and bankers from New York. To escape the Northern cold, they often bought multiple plantations and built winter homes or hunting estates.

Hobcaw Barony was the winter retreat of financier and advisor to six presidents, Bernard Baruch. In 1905, he bought its 17,500 acres which included 14 rice plantations. He built a magnificent home and according to its guest book, hosted luminaries like Charlie Chaplin, Guggenheim, Pulitzer, and Churchill. Franklin Delano Roosevelt, spent a whole month recuperating at Hobcaw House, and bedrooms are named for both him and Churchill.

Baruch’s daughter, Belle, was a noted athlete who excelled as an equestrian, sailor and hunter, winning many awards in Europe. But she never achieved her dream of competing in the Olympics. Olympic equestrian events were then closed to women.

Like her father, she so valued this part of South Carolina that she established the Belle W. Baruch Foundation to ensure that the pine forests, salt marshes, and cypress swamps of Hobcaw Barony would remain pristine and protected in perpetuity. In fact, two universities actually do ecological research on this land.

But one can still take a tour of the estate and see the magnificent homes of Baruch and of his daughter. Perhaps most compelling on the tour are the now empty homes of Friendfield Village. When Baruch bought the land, the original slave quarters here were still home to descendants of the men and women who had worked on Friendfield Plantation’s rice fields. Baruch hired them all, and apparently provided schooling for the children as well as medical care for the community.

Although the records have been lost, it’s thought that this was where Michelle Obama’s great great grandfather once toiled. Records show Jim Robinson was one of those who remained in the village on the estate after the Civil War, working as a sharecropper and living in the old slave quarters with his wife, Louiser, and their children.

These small, one-room homes, with no running water or electricity, would once have housed as many as 10 slaves, with the children sleeping in a tiny loft overhead. The guide points out the remnants of blue paint on the buildings. This distinctive colour is haint blue, used because evil spirits do not like water, so painting spaces to look like water apparently keeps them away. In fact, many of the early Georgetown homes, even those belonging to white plantation owners, used haint blue for their porch ceilings. It’s now a standard colour at Sherwin-Williams.

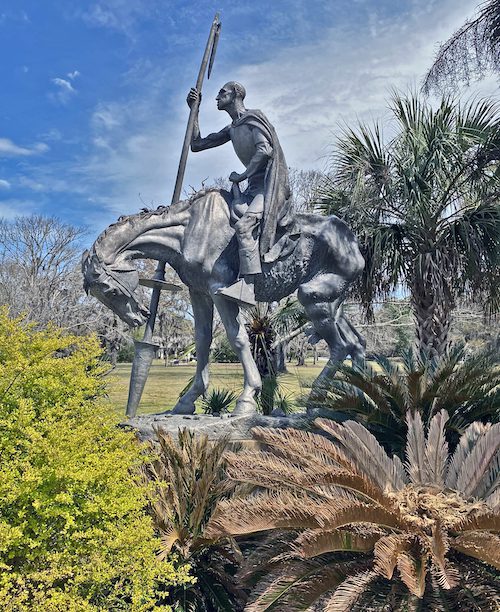

In 1930, another wealthy New Yorker, Archer Huntingdon and Anna Hyatt Huntingdon, one of America’s foremost sculptors of the 20th century, bought 9,000 acres which once encompassed four plantations. Huntingdon Beach State Park now stands on this land, which Archer decreed had to be set aside to protect wildlife and migrating birds. Indeed, the park and the beach are a magnet for nature lovers. A walk along Alligator Alley here provides an opportunity to see these reptiles in their natural habitat. And the spring and fall migrations bring almost as many birders as birds.

Also in the park stand the remains of Atalaya, an unusual Moorish-Revival style castle. This was the Huntingdons’ winter retreat. A tour of the property reveals some curious features. There’s an enormous workshop for Anna, many of whose sculptures were life-sized. Outside are the cages where she kept animals including bears, horses, monkeys, and even a leopard, which she would use as models. There’s an extensive study where Archer wrote poetry, and coordinated the plans for the many museums and institutions he established during his lifetime.

But it’s what isn’t to be found in Atalaya that is remarkable. There are no reception rooms or guest rooms. Patently this pair didn’t often entertain visitors.

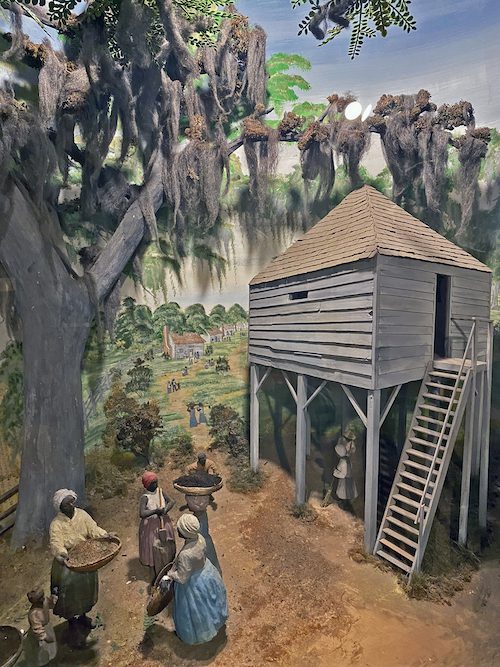

Also on their land is Brookgreen Gardens, a beautifully landscaped sculpture park, designed by Archer to showcase the work of his wife, as well as the art of many other American sculptors. In one part of the parkland, the history of rice cultivation is described through displays of plantation life. And a fascinating boat tour along a small preserved rice field offers a graphic picture of just how gruelling was the task of carving these fields from cypress swamps infested with biting insects and dangerous water snakes.

In fact, conditions in the Lowcountry during the growing season were not hospitable; malaria and yellow fever were common. So most white planters left the running of their plantations to overseers. The result was the growth of a culture which encompassed many different African tribal languages and traditions with little white input.

The descendants of these slaves, known as the Gullah, still live in the Lowcountry. They have preserved strong African elements in their language and culture. Indeed, the Gullah are known for preserving more of their African linguistic and cultural heritage than any other African-American community in the United States. And South Carolina cuisine includes dishes like red rice, shrimp and okra, and corn cakes, all of which originated in Gullah kitchens.

One distinctly Gullah handicraft is the sweetgrass basket. Along Highway 17, between Georgetown and Charleston, where many stalls display beautifully wrought baskets, I met Miss Mazie. Her creations are intricate and as with all such baskets, are so carefully woven, they last for decades. A nurse when she was younger, Miss Mazie is content now to sit in her tiny hut and weave these pieces of art. When asked how she learned to make them, she says with pride, “I’ve been making these since I was a young girl. It’s just part of my heritage.” Mazie’s baskets are for sale at the Georgetown County Museum, but watching her at her craft, and chatting with her as she works, breathes life into this centuries old skill.

In fact, it’s worth exploring all this history along Highway 17 between Charleston and Myrtle Beach, where this road is called the King’s Highway. This was its original name and it was more than 1,300 miles long, constructed between 1650 and 1735 to connect Boston and Charleston. While it’s tempting to simply step on the gas, don’t miss the art in Brookgreen Gardens, the charm of Georgetown, or the fascinating history at Hobcaw Barony or Hampton Plantation.

Stop at one of the stalls along Highway 17 and buy a sweetgrass basket from Miss Mazie and her fellow weavers for significantly less than you’ll pay in the markets of Charleston. And take some time to appreciate this small stretch of Highway 17 as it moves through South Carolina’s Lowcountry, where fortunately, far-sighted people have fought to ensure the history and unique character of this landscape will never be gone with the winds of change.

South Carolina Lowcountry Accommodations Map

Planning a visit to South Carolina’s Lowcountry? Check out this interactive map to different accommodations available in South Carolina’s Lowcountry.

Disclaimer: There are affiliate links in this post. If you make a purchase after clicking on one of these links, we may receive a small commission at no extra cost to you. This commission contributes to paying our writers for their storytelling. We only post links to things that we ourselves have tried.

Leave a Reply