In the far North of Russia in remote communities, like the village of Meynypilgyn on the Bering Sea, people like Norik, a Kereks fisherman, work to keep the indigenous Kereks culture alive along with Kereks traditions, honouring the spirits of their Kereks ancestors.

The Village of Meynypilgyn, Russia

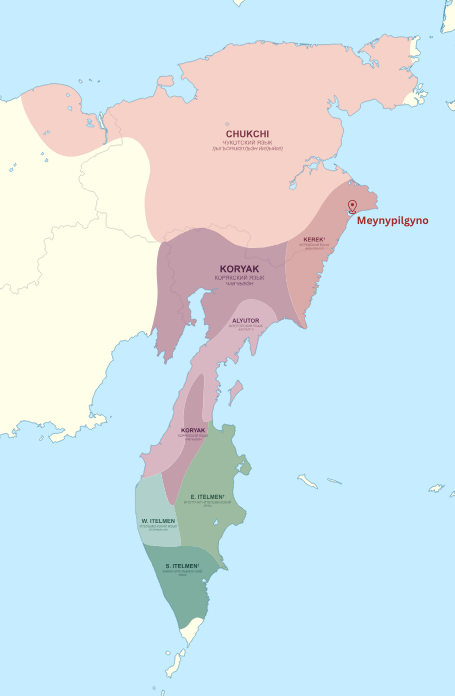

On the shore of Mayn Channel connecting Lake Vaamochka and Lake Pekulney, separated from the Bering Sea by a river and a spit, lies the small village of Meynypilgyn, in Russia’s far North, meaning “Big Mouth” in the local language. Located 200 kilometres south of Anadyr, the capital of Chukotka, the village is accessible only by helicopter, which arrives 2-3 times a month, and seasonally by boat. Here, amidst the rugged beauty of the Bering Sea, lives Norik, a fisherman and one of the few remaining self-identified Kereks— a nearly extinct indigenous people of Russia. While some consider the Kereks vanished, Norik and a few others keep their traditions alive. In Meynypilgyn, Norik keeps Kereks culture alive amongst the Chukchi people.

The Last Kereks

The Kereks, who call themselves “seaside people,” once thrived in Meynypilgyn, part traditional lands pre contact. By 2021, only 23 people identified as Kereks in the Census. Ethnologist Konstantin Klokov spent a decade studying the Kereks, noting their gradual assimilation into the Chukchi community. “During censuses, inexperienced enumerators recorded Kereks as Chukchi. No one calls themselves Kerek anymore, but they’ve simply blended with the Chukchi,” Klokov explains. Other accounts also suggest that many Kerek were assimilated into Koryak people too.

It should also be noted that data from Russia’s 2021 Census has been called into question, as was noted in a RadioFreeEurope article by Robert Coalson. “The number of people who refused to provide an ethnic identification grew substantially,” Russian sociologist Igor Yakovenko said. “This is a result of growing xenophobia. People understand what sort of consequences there might be in the future — better not to say anything, just in case.”

The Spring Ritual in Meynypilgyn, Russia

Every Spring, Norik and the villagers in Meynypilgyn perform a vital ritual: digging out the river mouth to help fish reach their spawning grounds. The channel, stretching 30 kilometres, is blocked by sand and ice in winter. Clearing it by hand ensures the sockeye salmon can enter the river. “If we don’t dig, the fish won’t spawn, and the village won’t have food,” says Norik. This tradition, passed down through generations, is a testament to their deep connection to nature.

Norik’s Story

Norik, whose name means “sockeye” in Chukchi, is a weathered fisherman with a profound respect for his heritage. Dressed in traditional reindeer fur clothing during the Spring ritual, he moves with the confidence of someone who knows the land intimately. “The ice hides the riches of the water,” he says, reflecting on the traditions of his ancestors and the challenges of preserving them in a changing world.

Tools and Techniques for the Spring Clearing Ritual

The Meynypilgyn villagers use shovels, wooden picks, and long stakes to break the ice. Some tie ropes to heavy chunks to drag them away. It’s backbreaking work, but the community works together, driven by necessity and tradition. Norik acknowledges the inefficiency of manual labour. “I’ve suggested using a bulldozer, but many fear it would disrespect our ancestors and anger the spirits,” he says.

Celebrating the Arrival of the Sockeye Salmon

When the channel is cleared, water rushes in, and the sockeye salmon begin their journey upstream. “It’s a celebration for the village,” Norik says. Families fish for a month, drying their catch on racks along the shore. The sockeye is vital for survival, providing food and a modest income. Yet, the villagers’ commitment to tradition often outweighs practicality. “We could make life easier, but our ancestors’ ways matter deeply to us,” Norik explains.

Fishing – Central to the Kereks’ Way of Life and Survival

Fishing has always been central to the Kereks’ way of life. Historically, the Kereks people hunted seals and walruses with chutchym (arrows), spears and kaluvianana (clubs). Today, the village of Meynypilgyn relies on modern fishing techniques, but the catch is primarily for local consumption. “We can’t export much. The helicopter only carries small packages of caviar to Anadyr,” Norik says. Despite the abundance of fish, the village remains isolated, with no roads or regular transportation.

Life in the Village

Meynypilgyn has a cultural centre, a school, a hospital, and even a small museum. Yet, the population is dwindling, with only about 335 residents remaining (based on data from 2023). In summer, villagers gather berries, mushrooms, and bird eggs, while in winter, they hunt seal and fish through the ice. The village is a blend of tradition and modernity, but lacks the infrastructure of urban living.

The Disappearing Kerek Culture

The Kereks were unique in their believes and societal structure. Women often led households and served as shamans, guiding their communities spiritually and practically. Children were revered as reincarnations of ancestors, and their names were chosen from maternal lineage. These traditions, however, have faded as the Kereks assimilated into Chukchi culture and Koryak culture. “We’ve lost much, but we still honour our ancestors,” Norik says.

Legends and Spirits

The Chukchi and Kereks share a rich mythology. They believe in spirits that inhabit the land, sea, and sky. Sacrificial sites with walrus skulls and whale bones dot the landscape, offerings to the spirits that govern their world. “The tundra is alive with forces that can help or hinder us,” Norik explains. These beliefs shape their rituals and daily lives, connecting them to their ancestors and the natural world.

The Future of Traditions

Norik is torn between preserving traditions and embracing modernity. “We could use machines to clear the channel, but it feels wrong,” he says. Yet, he understands the need for change. The village has already adapted some rituals, replacing live reindeer sacrifices with figurines made of ritual materials. “We’re not stuck in the past, but we must honour our ancestors as we move forward,” Norik reflects.

The Spirits of the Tundra

Walking along the river, Norik points out a knife with a twig placed on top. “It’s a sacrifice to the spirits. You must never take it,” he warns. The villagers believe that every object in the tundra could be an offering, and disturbing it brings bad luck. “If you need something, leave a replacement. Otherwise, the spirits will remind you of their presence,” Norik says. These rituals, though fading, remain a vital link to their heritage.

The Legacy of the Kereks

The Kereks may have disappeared as a distinct people, but their spirit endures in Meynypilgyn. Norik, as the last Kerek in Meynypilgyn, feels the weight of preserving their legacy. “As long as we honour our traditions, the spirits of our ancestors will watch over us,” he says. In this remote corner of Chukotka, the past and present intertwine, offering a glimpse into a people and a culture that refuse to be forgotten.

[…] The Last Kereks: A Story of Tradition and Survival in the Far North Russia […]