Marvelling at Japan’s traditions of courtesy and respect, Liz Campbell explores the sacred believes that shape this country through the shrines and temples in Japan.

Japan’s Traditions of Courtesy and Respect

Hands have been washed, shoes removed, and a coin tossed in the offering slot. Approaching the sacred place with reverence, each supplicant bows twice, claps twice, quietly offers a brief prayer, and finally bows deeply once more. Then each moves respectfully away to make room for the next. This is part of Japanese culture at shrines and temples in Japan.

This formality in devotion is typical of many interactions in Japan, where above all, harmony and civility are valued. Here, a greeting is a bow, and deference to elders is ingrained, whether in shrines and temples in Japan or just enjoying everyday life in Japan. Remarkably, in this ultra-modern country, traditional gestures of courtesy and respect remain the hallmarks of social interaction between all ages. And this courtesy extends to visitors. Indeed, it may be one of the reasons Japan is one of the most visited countries in the world. I find myself wondering, is it religious precept that dictates this?

Religions that Shaped Japan

Shintoism was the traditional religion of Japan until the 6th century, when Buddhism was introduced by Korean King Seong of Baekje. He sent a gift of an image of Buddha and some of his writings to Emperor Kinmei. The Japanese court welcomed and encouraged the acceptance of Buddhism which was adopted throughout the country, and the new religion grew harmoniously alongside Shintoism. This is perhaps not surprising as there are many similarities.

Neither Shintoism or Buddhism has a singular Creator or God, but multiple deities. Neither Buddha nor the deities are actually worshipped. Instead, respectful homage is paid to the sacred. Both offer traditions and practices to follow in order to lead a good life. And, unusually, neither demands complete allegiance. In fact, the majority of Japanese actually subscribe to both to some extent. Surely this very unique approach to the sacred is what encourages conformity, diligence, and social harmony.

Shrines and Temples in Japan

In Japan, there are about 80,000 shrines, and an almost equal number of temples. While in other parts of the world, temple and shrine might be interchangeable terms, in Japan, a temple is Buddhist and will usually have a statue of Buddha. A shrine is distinct to Shintoism – easily identified by the torii gates at the entrance which divide the secular from the divine. Visiting shrines and temples in Japan provides a unique insight into Japanese culture.

Shrines Are All About Nature

Fushimi Inari-Taisha Shrine

Bright vermillion torii gates welcome visitors to Fushimi Inari-Taisha Shrine in Osaka. Though few foreign visitors do this, it’s respectful to bow and keep to one side walking through them; the centre path is reserved for the sacred.

On this hot day, it’s a long way uphill, but dozens more, smaller torii form shading tunnels through which the faithful walk up Mount Inari. They perform this trek in homage to Inari, the kami (deity) of foxes, fertility, tea, sake, rice, agriculture, and worldly success. Two huge fox sculptures representing Inari stand on either side of the entrance torii. And on the grounds of this shrine are many more fox statues.

Inari is just one of several million Shinto deities, one for virtually everything, including the weather. But as Inari’s purview patently includes several things of consequence to health and prosperity, she is one of the most important kami, and paying homage to her is a prayer for the blessing of plenty.

Significantly, while there might be sacred areas dedicated to specific kami, shrines also include areas where visitors can encounter nature. Early mystics sought healing and strength from the natural world, and for centuries, followers of Shinto have practiced meditation while walking through forests.

It’s probably not surprising then, that in the 1980s, tech-centric Japan found new enthusiasm for this ancient practice. Perhaps from a wish to reconnect to, and be inspired by nature, Shinrin-yoku, or ‘forest bath’ was embraced by the Japanese, and actually spread to many other parts of the world. Happily, this contributed to the protection of the country’s forests. Today, Japan is one of the most forested countries in the world; about two-thirds of the land is covered with forest. Perhaps too, this affinity with nature kept young people connected to Shinto shrines where specific trees often have special meaning.

At Fushimi Inari-Taisha Shrine the remains of a pine tree, its roots exposed and appearing to kneel, is a focal point for the faithful. It is called Neagari-no-matsu which translates to ‘pine tree with uplifted roots’. But a homonym of neagari can also mean ‘price rise’, and of matsu can mean ‘to wait’. This tree is said to have divine power to bring success and good fortune to those in business, especially related to stocks and securities. Understandably, many come here to offer homage. After reading the information board, I notice several foreigners pause to offer homage too.

Kitaguchi Hongu Fuji Sengen Jinja Shrine

In fact, many shrines have trees with spiritual significance. Near Tokyo, at the northern base of Mt. Fuji, the Kitaguchi Hongu Fuji Sengen Jinja Shrine is home to ancient cedar and cypress trees. It’s awe-inspiring to walk to the sacred areas along an avenue lined by these giants. The thousand-year-old Fuji Taro cedar and the twin-trunked Fufu Hinoki (Couple Cypress where many couples pose for a photo) are revered as symbols of nature and immortality. Stout ropes have been tied around their trunks, and the faithful leave messages tied to strings near the base. One of these simply says in English, ‘Peace’– a universal message, or a devout wish for conjugal accord?

Meiji Jingu Shrine

Marriage is an important rite at one of Japan’s most popular shrines. Tokyo’s Meiji Jingu Shrine and the adjacent Yoyogi Park were built in 1920, dedicated to the deified spirits of Emperor Meiji and his consort, Empress Shoken. During the important New Year celebrations, more than three million visitors attend first prayers here. Dozens of kegs of fine sake and vintage Burgundy wine barrels form unusual displays on the road leading to the sacred places here. Apparently these are empty (a relief to oenophiles). The sake barrels are symbolic offerings to the gods, while the wine barrels represent Emperor Meiji’s role in modernizing Japan and embracing foreign influence.

Here too, trees play an important role. About 100,000 trees were donated from regions across Japan in order to create the distinctive forest here. Two camphor trees planted in 1920 have grown to great height and are coupled by a stout rope. Known as Meoto Kusu – Husband and Wife – they are considered sacred and represent marital harmony. Perhaps for this reason, Meiji is a favourite shrine for weddings. Indeed, we watched as, in graceful unity, an elaborately dressed couple formally bowed to one another and to the Shinto priest performing their wedding rites.

Glorious Temples Promote Peace and Compassion

The Golden Temple, Kinkaku-ji

Buddhist temples are among the most striking buildings in Japan. A magnificent example is near Kyoto. The Golden Temple, Kinkaku-ji, was built in 1408 as a retirement residence for the Shogun Yoshimitsu. After his death, his will directed it be turned into a temple. Sadly, it has burned down and been rebuilt several times since. In a rather dramatic turn, the last fire, in 1950, was begun by a mad monk. But five years later, Kinkaku-ji was rebuilt exactly as before.

It’s aptly named. That rich colour isn’t paint; the top two levels are covered in gold leaf and glow gently, even on the most overcast days. Appropriately, given its incendiary history, a golden phoenix sits on the roof.

Inside is a seated Kannon Bodhisattva (Goddess of Mercy) surrounded by statues of the Four Heavenly Kings. Unfortunately, we can’t see them as entry is forbidden. However, we can stroll the temple gardens which are as they were nearly 600 years ago, when Yoshimitsu walked through them. Here, surrounded by trees, is the Anmin-taku pond, with a miniature stone pagoda on an islet in its centre. This pond is sacred, as it never dries up, even during droughts. Thus the faithful come here to pray for rain.

Todaiji Temple

Just south of Kyoto in Nara, Todaiji must be one of the most appealing temples, partly because of the charming Nara deer that are everywhere on its grounds. Buy some special crackers to feed these gentle creatures and they become immediate friends. Constructed in AD752, this temple is historically significant as it was the head temple of Buddhism when Nara was the capital. The capital was later moved in order to remove undue influence by its monks.

The enormous wooden Nandaimon Gate, stands at the approach to Todaiji. Its broad threshold separates the secular world from the sacred realm, and custom dictates that one must step over it; stepping on it is disrespectful.

On either side of the gate, behind protective barriers, stand two menacing statues representing the two Guardian Kings. Dating to the 12th century, both this gate, and the statues are designated as national treasures.

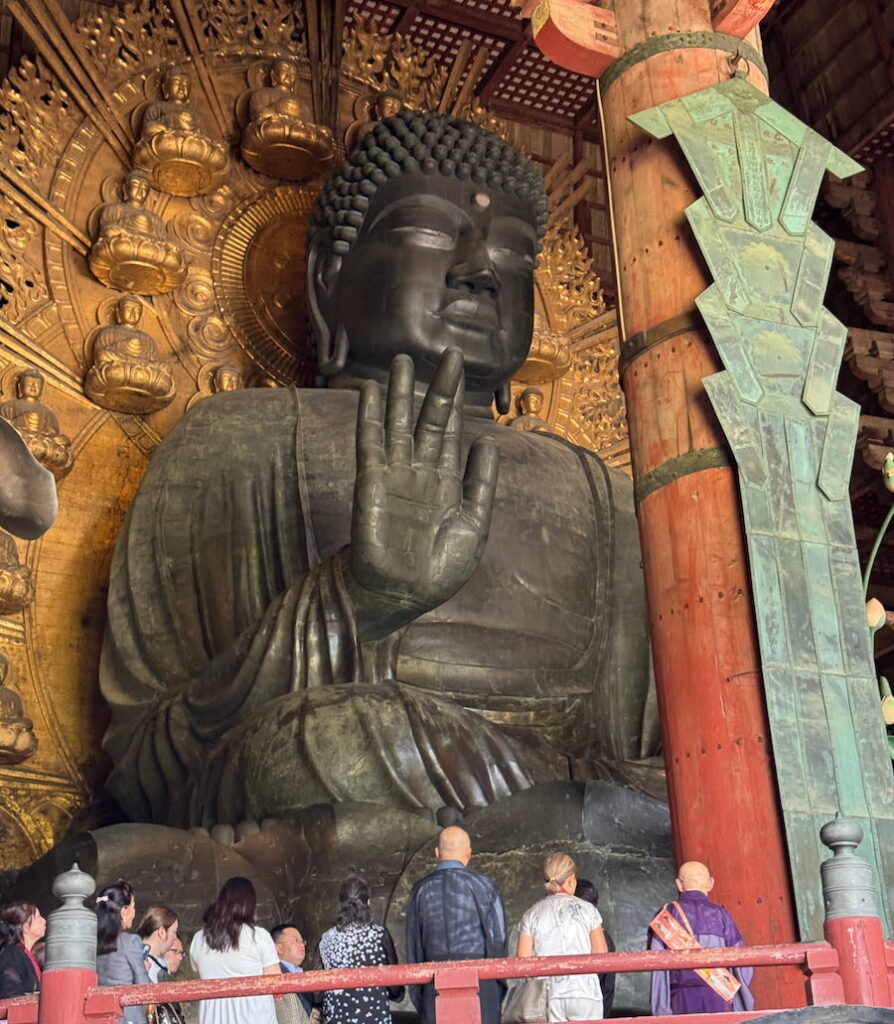

The splendid main hall at Todaiji houses Daibutsu, one of Japan’s largest bronze Buddha statues; his open hand alone is human sized. He sits flanked by two rather intimidating Bodhisattvas. A popular attraction inside is a pillar with a hole in its base that is the same size as the Daibutsu’s nostril. It is said that those who can squeeze through this opening will be granted enlightenment in the next life.

I didn’t attempt the impossible, but I did stop outside to rub Binzuru’s right knee, then my own. One of the interesting characters in the Buddhist panoply of deities, Binzuru can often be found sitting outside temples and is said to be a healer. If some part of your body is sore, you rub that part on him, then rub the sore part on yourself. I can report that my knee did feel better the next day.

Sensoji Temple

As with the Golden Temple, the Goddess of Mercy is at the heart of the oldest Buddhist temple in Japan. According to legend, in the year A.D. 628 two brothers fished a statue of Kannon out of the Sumida River. They returned it to the waters, but it turned up again. Seventeen years later, Sensoji, also known as Asakusa Kannon Temple, was erected nearby in her honour in the Asakusa district of Tokyo. Sadly, here too, the public may not see the Goddess of Mercy. The famous statue was enclosed inside a miniature temple with several locks; not even the chief priests of Sensoji may view it.

At Sensoji Temple, a huge incense burner stands between a five storey pagoda and the main hall. Incense burners are usually found on the grounds of temples and the faithful can purchase incense sticks to light. This too has a ritual. Once alight, one should extinguish the flame by waving the hand, not by blowing. The hand may then be used to fan smoke towards oneself for healing purposes. At Sensoji, whole bundles of incense are lit at a time, so the smoke can be prodigious.

More than 30 million visitors pass through its two grand entry gates annually making Sensoji one of the country’s most visited temples, and the streets surrounding it have become popular shopping areas for kimonos, fans and other traditional Japanese gifts.

Nipponzan-Myohoji Temple

Just 100 km south of Sensoji is the Fuji Bussharito Heiwa Park (Peace Park) in Gotemba. The Nipponzan-Myohoji Temple here is very significant, and a must to visit, not least because some of the most spectacular views of Mt.Fuji can be found here on a clear day. We were sadly disappointed as the day was both overcast and rainy so we didn’t see the elusive mountain, said to be visible only a third of the year. However, much to our delight, Fuji graced us with a brief viewing on another day, coyly peeking from behind low clouds.

However, even on a grey day, this park is well worth visiting. Built to promote the Buddhist tenet of peacemaking, it brings this concept to global fruition, uniting a number of Asian countries in a message of world peace. Its focal point is Nihonzan-Myoho-ji’s shining white stupa with golden Buddha images set into niches at its four sides. Most importantly, inside rest some of the Buddha’s bones, presented by late Indian Prime Minister Nehru of India. Guardian dogs and lions, gifts of a number of Asian countries – Hong Kong, Myanmar, Thailand, and more – line the path approaching the temple. Despite some of their fierce expressions, the message of peace rings out loud and clear in this park.

A wander through the grounds reveals a Peace Bell flanked by two white lions. Further on, a golden statue of Kannon stands in front of a small temple. The persistence of this goddess of mercy in so many Buddhist temples emphasizes the importance of compassion in Japanese society.

In a world which seems to be losing sight of such values, Japan presents an oasis of ahimsa (doing no harm). After my meanderings through shrines and temples in Japan, it seems my question has been answered. Japan’s two faiths do play a role: Buddhism’s emphasis on discipline and peace, and Shinto’s respect for, and harmony with nature, seem to have produced a uniquely tolerant and kind society, united by its truly enlightening shrines and temples.

Leave a Reply